Bayes' Rule

Recommended Reading

This is Bayes’ Rule:

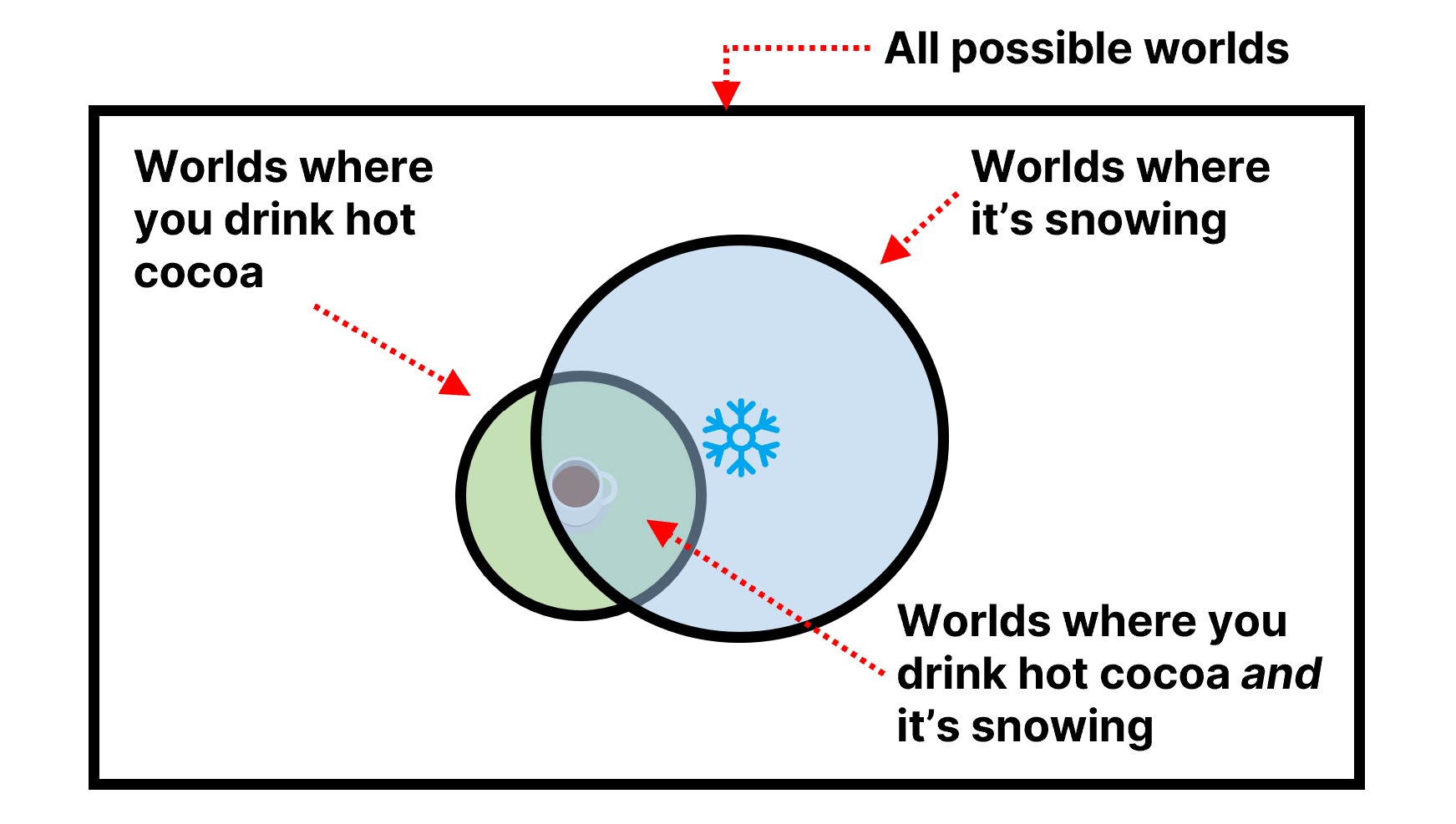

Let’s reframe this in terms of snowfall and hot cocoa:

The left-hand-side is called the posterior which we try to infer based on some observation. In this case, I am trying to infer the likelihood it is snowing if I observe you drinking hot cocoa. We break this inference into three factors:

- : The chance that you drink hot cocoa when it really is snowing.

- : The overall chance that it snows.

- : The overall chance you drink hot cocoa whether it is snowing or not.

Let’s assume these values are 0.8, 0.2, and 0.3 respectively, and see what the numerator represents. It snows 20% of the time, and in that 20% you drink cocoa 80% of the time. Multiplying these together gives the overall chance you drink cocoa and it’s snowing as 80%×20% = 16% (80% of 20% is 16%).

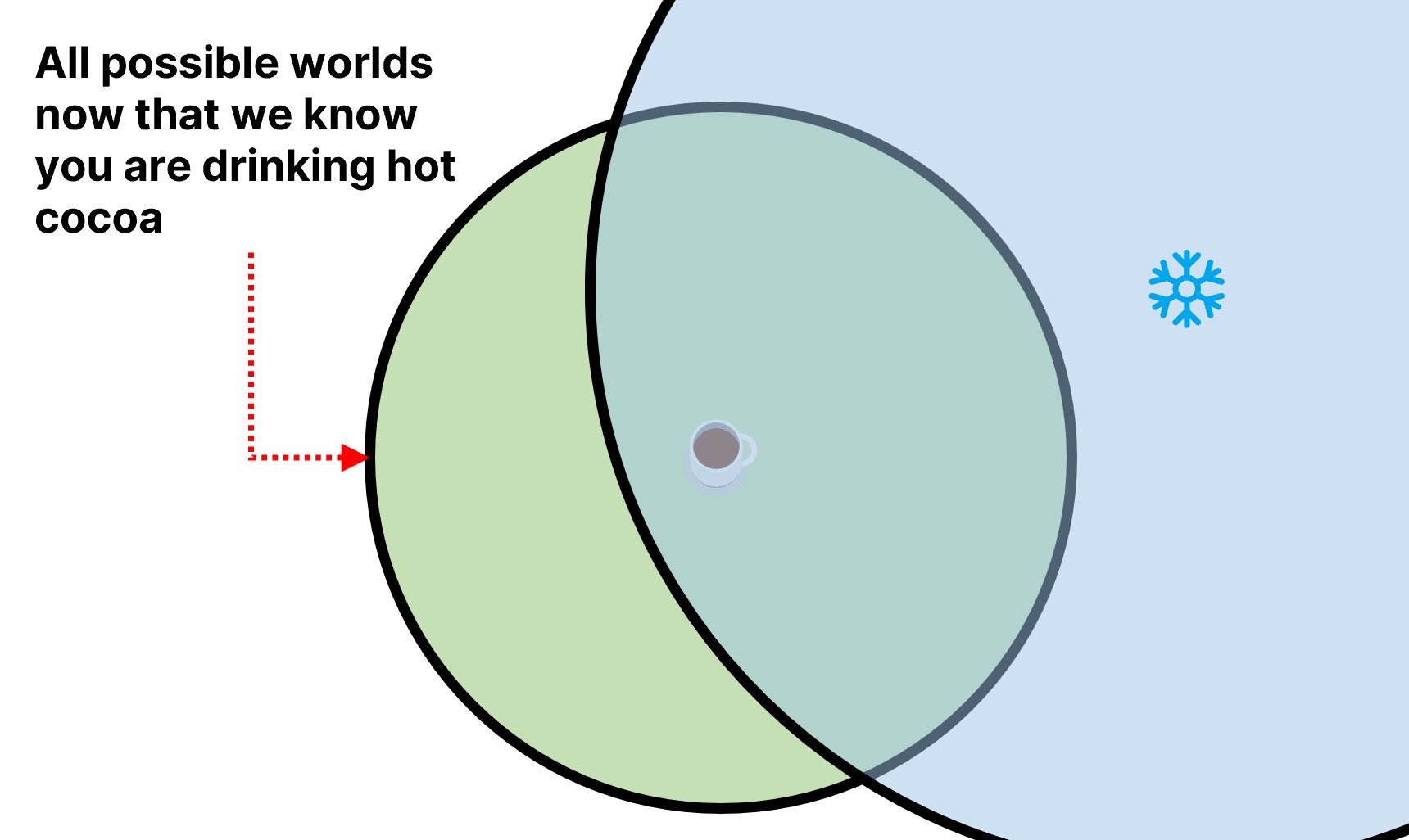

However, I don’t really care about this value, because I am starting from the premise that I know you are drinking hot cocoa. That shrinks my scope to only the possible worlds that involve you drinking hot cocoa:

While the combined chance was just 16% before, I need to jack up this probability because I’ve shrunk the possible worlds down. Now the chance of snowing is much higher—it takes up more of the remaining possible worlds that already involve you drinking hot cocoa. I can get the exact number by dividing by the 30% chance we end up in a world where you drink hot cocoa to get 16% / 30% = 64% chance it’s snowing. Before, I took 16% out of the possible 100% of worlds. Now I rescale to take that 16% out of the 30% of world’s with hot cocoa. Using the knowledge that you are drinking cocoa, I can infer a higher chance that it is snowing.

In one sense, Bayes’ Rule gives us a way to switch up our reference “world” based on known information. For example, we could’ve started from the opposite premise and asked, “Given that it is snowing, what’s the chance you’re drinking hot cocoa?” Of course, we manually set this to be 80% in the previous example, but we could’ve set up the problem to infer it as well:

In this case, we once again use the numerator to figure out the joint probability and then rescale things to the world in which we know it is snowing. The joint probability remains 16%, but since the “it’s already snowing” worlds make up 20% of all possible worlds, we divide the 16% out of 20% to get 80%, matching the value we had set before.