Let's Calculate a Lagrange Point For Fun

The James Webb Space Telescope needs to be consistently shielded from the light and heat of the Sun and that reflected by the Earth. Ultimately, we need two things:

- Consistent communication contact with Earth

- Orientation that never puts the Sun or Earth in the telescope’s field of view

The best place would be somewhere on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun in an orbit with the same period (duration) as the Earth. This would keep the object in the same position relative to the Earth and the Sun, allowing us to predictably point it away from both and always stay in contact.

A Brief Review of Orbital Mechanics

We need to know a few things to solve this problem. First, since moving objects don’t change direction without an outside force,1 if an object moves in a circle (constantly changing direction), there must be a constant force acting on it. We call this the centripetal force. It’s pretty easy to calculate:

\[F_c = \frac{mv^2}{r}\]For objects in orbit, gravity provides the centripetal force. We can calculate the force of gravity with:

\[F_g = \frac{Gm_1 m_2}{r^2}\]where $G$ is the universal gravitational constant, $m_1$ and $m_2$ are the masses of the objects, and $r$ is the distance between them. Since gravity is providing the centripetal force, we can then set these two equations equal to each other, since the forces should be equal. I’ll use $M$ to represent the mass of the body being orbited and $m$ to represent the mass of the thing doing the orbiting.

\[\frac{GMm}{r^2} = \frac{m v^2} {r}\]Before we go further, it isn’t very intuitive to work with velocity $v$ in this expression. It would be more convenient to instead think of the angular velocity of the object, which is directly connected to how quickly the object completes an orbit.

\[\frac { v\text{ meters}}{1 \text{ second}} \times \frac{1 \text{ orbit}}{2\pi r \text{ meters}} \times \frac{360 \text{ degrees}}{1\text{ orbit}} = \frac{180 v}{\pi r}\ \text{degrees}/\text{second} = \omega\]Next, we solve for $v$ so we can substitute that into our force equation:

\[v = \frac{\pi r \omega}{180}\]Substituting we get

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{GMm}{r^2} &= \frac{m (\pi r \omega / 180)^2} {r} \\ &= \frac{m \pi^2 \omega^2 r^2}{180^2 r} \\ &= \frac{m\pi^2\omega^2r}{180^2} \end{aligned}\]We can simplify this even more since $m$ appears in the numerator of both sides–we can divide it out.

\[\frac{GM}{r^2} = \frac{\pi^2\omega^2r}{180^2}\]This is great–it means that our result doesn’t depend on the mass $m$ of the orbiting object and will hold for any spacecraft of any size.

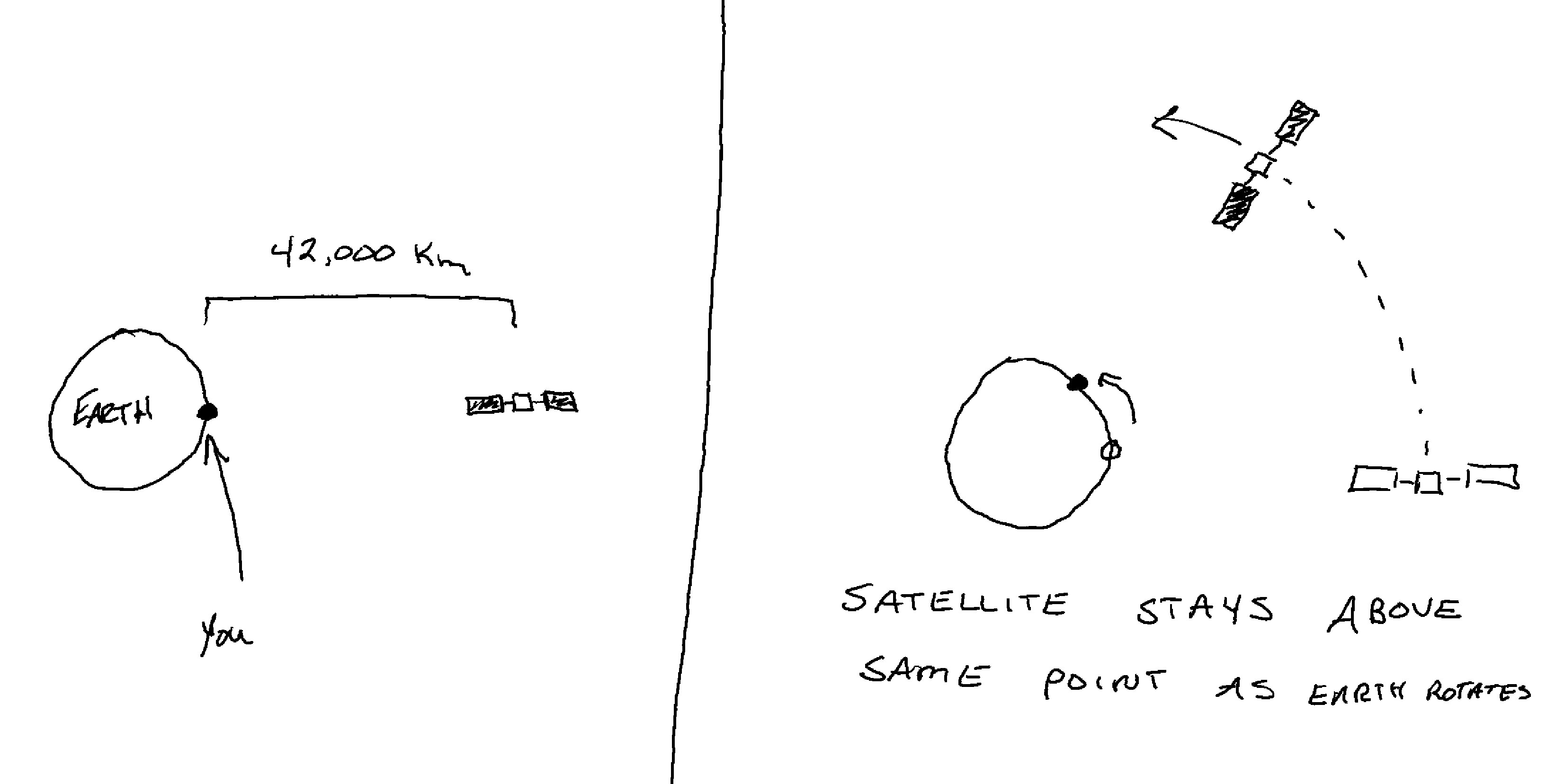

Geostationary Orbits

Let’s see how we can use this equation with a simple example. We want to launch a satellite to the right altitude such that it moves at the same speed that the Earth rotates. It will appear to hover over one location–we call this a geostationary orbit. The Earth rotates at a rate of once per day, or $360 \text{ degrees} / 86400 \text{ seconds}$ which is $0.0042\text{ degrees} / \text{second}$. Next, we need to solve for $r$:

\[\begin{aligned} r^3 &= \frac{180^2GM}{\pi^2\omega^2 } \\ \implies r &= \left(\frac{180^2GM}{\pi^2\omega^2 }\right)^{1/3} \end{aligned}\]We know that $M = 5.97 \times 10^{24} \text{ kg}$ and $G = 6.67 \times 10^{-11}\ \text m^3\text{kg}^{-1}\text s^{-2}$,2 so we can plug everything in and get:

\[r = 42,000 \text{ km}\]Subtracting 6380 km for the radius of the Earth, we find that a geostationary orbit has an altitude of 35,800 km above the Earth’s surface (22,200 miles).

In the original problem, though, we want to find an orbit around the Sun that matches the Earth’s year, so it always stays in the same relative position with the Earth. At first, this might seem like an impossibility. To keep up with the Earth, wouldn’t the object need to be in the exact spot the Earth is in?

Yes, except we can’t ignore the affect of Earth’s gravity in addition to that of the Sun–there are now three objects to keep track of: the Sun, the Earth, and the spacecraft.

Adding the Sun

We’ll start by updating our gravity-centripetal force equation to include the Sun on the left-hand (gravity) side:

\[\frac{GM_s}{r_s^2}+\frac{GM_e}{d_e^2} = \frac{\pi^2\omega^2r_s}{180^2}\]$M_s$ is the mass of the Sun, $M_e$ is the mass of the Earth, $r_s$ is the spacecraft’s distance from the Sun, and $d_e$ is the distance of the spacecraft from the Earth. If we want to do 360 degrees around the Sun in one Earth year (the same speed at which the Earth is moving), we end up with $\omega = 1.14 \times 10^{-5} \text{ degrees}/\text{second}$. We also know that $d_e = r_s - r_e$ where $r_e$ is the radius of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun:

\[\frac{GM_s}{r_s^2}+\frac{GM_e}{(r_s - r_e)^2} = \frac{\pi^2\omega^2r_s}{180^2}\]We want to solve for $r_s$, which, it turns out, is not easy. Luckily, with some handy Python code, we find

\[r_s - r_e = 1.4\times 10^6\ \text{km}\]which is about 900,000 miles. Thus, if JWST flies to this point 900,000 miles away from the Earth, it can orbit the Sun with the same period as the Earth and stay in the same relative position. It will always be able to face away from both the Sun and Earth while staying in constant communication contact (nothing will be blocking it).

The Code

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import fsolve

gravity_const = 6.67e-11

mass_sun = 1.99e30 # kg

mass_earth = 5.96e24 # kg

radius_earth_orbit = 1.5e11 # meters

angular_speed = 2 * np.pi / (365.25 * 86400) # rad/s

def func(x):

return (

gravity_const * mass_sun / x ** 2

+ gravity_const * mass_earth / (x - radius_earth_orbit) ** 2

- (angular_speed ** 2) * x

)

guess = radius_earth_orbit + 1e3

out = fsolve(func, guess)[0]

distance_from_earth = out - radius_earth_orbit

print(f"{distance_from_earth/1e9:0.1f} ⨉ 10⁹ m")